Wait until I tell Mom about the surprisingly lax requirements to be the coroner of Lewis County, Washington.

It’s not merely the fact that lack of a medical degree of any kind is not a barrier to this job that involves determining the cause of death that makes one wonder if a page from the job description was lost. There’s the added bonus of not having to waste time going to the scene of the death one is investigating. At least, not according to Coroner Terry Lewis who didn’t feel that going to see where a woman was found shot to death on the floor of her closet was something that needed looking into. Way to save gas, Terry!

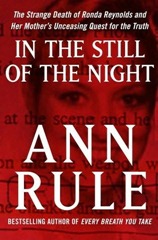

Be forewarned: In the Still of the Night is not the typical Ann Rule book. There is no satisfying ending with most questions answered. It isn’t even certain that a crime was committed unless you count possession of “Elvis Presley plates.” This isn’t a traditional true crime book either. It is the story of a parent determined to make law enforcement properly investigate her daughter’s death. The heroine thus is not the victim, it is her mother, Barb Thompson.

For me Ann Rule is at her best when telling stories about strong women. My favorite of her books all feature female murderers and Rule’s ability to understand them has always kept me coming back for more. When the victim is female and the killer male, Rule can go into beatification mode with numerous descriptions of the victim’s beauty and general saintliness. I can usually skim over that but I know it drives others crazy. There’s considerably less of that here and I think that’s because of Rule’s focus on Barb who is one tough, resourceful lady. What emerges is a story that is too common – the difficulty of getting justice without considerable financial resources at your disposal.

It’s also the familiar story of a man with little to recommend him who just about has to beat off the ladies just to make it through his own front door. Never having the experience of having a man announce to me on the first date that he was impotent I can say for certain that it would make me decline a second date but I’m pretty sure I could find something else to do. For Ron Reynolds, it worked as well as a marriage proposal.

While many of the elements of a true crime book are here, the lack of a conclusion is frustrating. Balance that against Anne Rule and Barb Thompson trying their hand as Cagney and Lacey only to find that few will talk to them and those that will won’t tell them the truth. “So much for our ability as investigators – or even likable strangers.” Don’t worry about it, Ann, as long as you’re willing to use your clout to highlight a miscarriage of justice you’ll always have your day job.

So, all in all, a bit of a disappointment for me. I admire Ann Rule’s commitment to this story but it’s not one I’ll be rereading any time soon.

Last Call: the rise and fall of Prohibition

Last Call: the rise and fall of Prohibition